Diana is always a welcome guest on the

Scribbler and we are pleased to have her back.

I have had the pleasure of reading Diana’s

trilogy of which Paper Roses is the third book in the series.

Beware –

the stories are extremely captivating. You will have to set aside your to-do-list

after you open the first pages.

If you missed Diana’s last visit, please go HERE.

Read on my friends.

Diana Stevan likes to joke she’s a Jill of all trades as she’s worked as a family therapist, teacher, librarian, model, actress and sports reporter for CBC television. Her writing credits include newspaper articles, poetry, and a short story in the anthology Escape. She’s also featured in Alex Pearl’s book 100 Ways to Write A Book. Conversations with authors about their working methods.

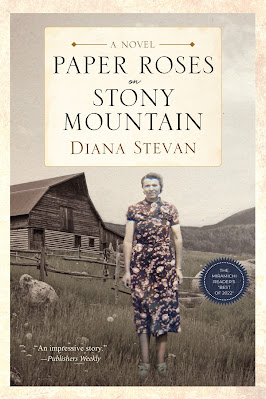

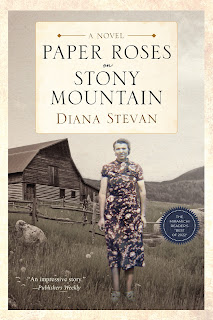

Her novels cross genres: A Cry from the Deep, a time-slip romantic mystery/adventure; The Rubber Fence, women’s fiction, inspired by her work on a psychiatric ward; the award-winning Sunflowers Under Fire, historical fiction / family saga based on her Ukrainian grandmother and her family’s life in Russia during WWI; and its sequels Lilacs in the Dust Bowl, and Paper Roses on Stony Mountain, set during the Great Depression in Manitoba and the early years of WWII. The latter novel was on The Miramichi Readers’ List of Best Fiction of 2022.

When Diana isn’t writing, she loves to garden, travel, and read. With their two daughters grown, she lives with her husband Robert on Vancouver Island and West Vancouver, British Columbia.

Working Title: Paper Roses on Stony Mountain

I chose this title because I wanted to maintain a flower theme for Lukia’s Family Saga, a biographical and historical fiction series. The flower theme started with the first book, Sunflowers Under Fire. Since the sunflower is the national flower of Ukraine and my story takes place during WWI, it seemed like a fitting title. The sequel, Lilacs in the Dust Bowl came about because I had a photo of my father holding a bouquet of lilacs in his hands in front of an old barn during the Great Depression. That photo became the cover of the sequel, which also made sense as his family appears for the first time in this novel. And the title of the last book in the series—which, by the way, can be read as a standalone like the other two—came about because while my mother was living with my father in Stony Mountain, she made paper roses to supplement their meagre income.

Synopsis: Paper Roses on Stony Mountain tells the story of how Lukia Mazurec and her

family fare as Ukrainian immigrants during the last years of the Great

Depression and the early years of World War II in Winnipeg and on the Manitoba

prairies.

Lukia’s dream of

family unity is crumbling, as one by one her children leave, forcing her to

make some hard decisions. Wars, typhus, drought and family losses could not

stop her in Ukraine. Will her children’s indifference in

Canada finally break her spirit?

The

Story Behind the Story: I’ve

had quite the journey writing this epic family saga, covering the years from

WWI to WWII, 1915-1943. When I wrote the first novel in the series, I thought I

was done. But readers were curious as to what happened to Lukia and her family,

so I wrote the sequel. Since there was so much to tell and show, I ended up

writing the third as well.

My mother loved

telling stories about her life. She was a natural oral storyteller, and I’m so thankful she made sure I knew not only the

hardships but also the joys of making lemonade out of the lemons that came her family’s

way. I know she’d be pleased I’ve strung her stories into a book, like pearls

on a necklace. I’m not sure how my father would feel, as he was a private man. But

because he loved my mother deeply and tolerated her openness, I suspect he’d

accept what I’ve written and embellished in this historical and biographical fiction.

A couple

questions before you go, Diana:

Scribbler: Can you tell us about the perfect setting you

have, or desire, for your writing? Music or quiet? Coffee or tequila? Neat or notes everywhere?

Diana: I love music, but I prefer quiet when I

write. With characters speaking through me and hurrying me along, I have enough

sounds running through my head. 😊

First thing

in the morning, I head to the computer with a cup of coffee. I keep it at two

and switch to tea and water in the afternoon. My desk is not neat. I have to

keep tidying it up, as I have a habit of writing notes on scraps of paper and

they pile up.

Scribbler: What’s next for Diana Stevan, the Author?

Diana: I’m hoping to launch a book of short stories loosely

based on my experience of growing up in rooming houses. I’ve also written a

pilot and the second episode for a limited series of Sunflowers Under Fire. With

the writers’ strike in Hollywood and everything at a standstill, I don’t hold a

lot of hope it’ll be produced. But I started writing screenplays in the 1990s,

and had an agent for a while, so I felt compelled to give it a try.

Thank you so much

for having me, Allan. Such a pleasure to be on Scribbler.

***It is my

pleasure, Diana. I truly enjoy your stories and thank you for those.

Here’s the first

chapter from Paper Roses on Stony Mountain:

A Curious Incident

|

|

Lukia believed there was nothing like the sun’s glow to dispel the darkest

of moods, but despite the warm rays on her skin, she could not shake the

feeling of foreboding that had come over her. She stopped weeding the vegetable

garden to push some loose strands of hair off her forehead, then stretched her

aching back and leaned on her hoe. Her daughter, Dunya, and daughter-in-law,

Elena, had their heads down as they hoed the rows nearby. Their laughter over

some shared joke punctuated the air, as did the honking of the geese flying

overhead. Lukia wished she could share their joy. She should have been working,

like them, with renewed vigor. From what she understood

from the news reports on the radio, the Depression was nearing its end. A

Depression that had given her nothing but grief ever since she’d immigrated

with her family to Manitoba in 1929—eight years ago. The hard times weren’t

over yet, but rising grain prices meant hope on the horizon. That should have

been enough to get Lukia dancing the kolomeyka

up and down the rows, but her thoughts were elsewhere.

Her sons continued to quarrel. Egnat’s frustration had grown

over Mike’s irresponsibility and his flirting with Elena. His wife had done nothing

to encourage Mike, but her gentle nature had charmed the younger brother, who

would often make excuses to help her with the children or some domestic chore

rather than work alongside his brother in the fields. And then, when he

returned drunk from the city with less cash than expected from the sale of

their grain or dairy products, there was bound to be a fight. Lukia had lost

count of how many times she’d pulled Mike aside to tell him to stop aggravating

Egnat, to stop visiting the beer parlour or the bootlegger, to stop

entertaining his friends and strangers, and to stop pestering Elena. No matter

what she said or how she said it, he didn’t listen.

Lukia stared into the distance, where Egnat sat on the

horse-drawn mower, cutting the pasture. He had tolerated so much, and yet he

never complained. Even when he had to build his father’s coffin on his

thirteenth birthday and help his mother raise his siblings. The problem was

Mike was simply too close in age to allow his older brother to be his guide. His

horns of envy threatened to tear her family apart.

As if she didn’t have enough grey hairs, there was also the

problem of Dunya, who was in love with a poor man. He’d stopped coming around a

year ago over some silly argument, but when her daughter ran into him the other

day in Winnipeg, she realized she still loved him and broke off her engagement

to a Russian fellow, a man of means who worked at the Winnipeg Stock Exchange.

Why did Dunya push Sergei aside and give up a chance for a good life? She hoped

Dunya would come to her senses. Immersed in thought, Lukia nearly tripped over

Puppy, who surprised her by charging out of the cornstalks, kicking up the dust

and making her cough.

“Puppy! What’s got you so excited? If you had my worries, you

wouldn’t be jumping like that.” She leaned down to pet the collie before

watching him scamper off to greet Dunya and Elena. Thrusting the hoe into the

soil again, she hacked away at the weeds as if they were hiding the answers to

all her problems.

Brooding over her

lost love, Dunya brushed her long hair, then sat on her bed in the room she

shared with her mother and her niece, Genya. She tried to make sense of what

had happened in Winnipeg. Peter

should’ve been standing there on the sidewalk when she came out of the

jewellery shop. She could have sworn he had been staring at her through the

window as she was picking out rings with Sergei. But when she ran out of the

shop to talk to him, there was no Peter in sight in any direction.

Confused, she wondered if Peter’s image had been a mirage. Or

a sign from God saying it was Peter she should marry, not Sergei, even though

Peter had broken up with her six months before. And who was she to argue with

God? She told Sergei their engagement was off and left him standing on the

sidewalk.

When she returned to the farm, she related this curious

incident to her mother. But instead of being understanding, her mother scolded

her. First, for breaking off her engagement to a successful man and then, for

thinking of eloping without her mother’s or priest’s blessing.

Unabashed, Dunya had shrugged and said, “Why are you so

upset? I didn’t get married.”

“Oy,” her mother said. “That’s all you have to say? My God,

how have I raised you?”

“I’m sorry, Mama.” Dunya knew better than to argue with her

mother.

She said good night to her mother, donned her nightgown, and

got down on her knees. After saying the Lord’s Prayer, she asked God for

another sign. “If Peter’s the one I’m supposed to marry, have him come back to

me.” Satisfied with her request, she climbed into bed and fell asleep thinking

of Peter.

A week later,

Dunya decided she couldn’t leave her future up to God alone. Though the day

promised to be hot, the kind the English called a scorcher, she went with Egnat in their wagon to Stony Mountain to

get some flour and other staples. It was usually her mother who went, but this

time Dunya offered to go, as she was hoping to run into Peter, who lived in the

village which had a federal penitentiary on the hill leading up to it.

About a mile before the village, they passed the farm where

the prisoners toiled. A large work gang in coveralls, their feet bound by

chains, were weeding and thinning the crop while a guard on horseback stood

watch. A few appeared younger than her. She thought their lives must have been

awful if they had to resort to crime to get ahead. She guessed some were

dangerous, or else why would they be bound like that and forced to do labour in

such a humiliating fashion?

As her brother drove the horses up the hill, past the

limestone prison—a massive structure that loomed forbiddingly over the highway

and the prairies—Dunya shifted in her seat uncomfortably. There was no escape

from the sun beating down on them. Her thighs stuck together in the unbearable

heat. She flapped her arms, hoping perspiration wouldn’t stain her dress and

spoil her appearance. She thought about what she would say if she ran into

Peter. Maybe he would be at Dan Balacko’s General Store, one of two stores in

the village. Dan’s was popular with the Ukrainian farmers; the other was

William McGimpsey’s, popular with the English. General stores were where locals

gossiped and discussed news and politics. She wondered what she should do if

she saw Peter there. Should she apologize for her part in their breakup? Should

she tell him she thought she saw him looking in the jewellery shop window?

Should she say she never really loved her Russian boyfriend and was no longer

engaged?

“You’re awfully quiet,” said Egnat as he drove past the

penitentiary. “Are you sick?”

If she were being honest, she might have said, sick in love with Peter, but she

replied, “No, I’m just thinking. You always complain I talk too much.

You should be happy I’m quiet.”

He snorted as he flicked the reins. “You’re right. It’s a nice

change when you’re quiet.”

She jutted her chin and looked ahead.

Outside Dan’s store, a couple of farmers stood around an old

truck, having a smoke. Egnat stopped to talk to them, while Dunya peered up and

down the gravel road, hoping to catch a glimpse of Peter. But all she saw were

two cars driving down the main street, which contained the Masonic Lodge, the

Canadian Legion, a modern school, and three churches.

She found some shade under the store’s eaves and stood in

back of the farmers, who didn’t seem to mind the sun.

Egnat pulled a hand-rolled cigarette from his shirt pocket

and lit it. He said to the stout farmer in baggy overalls, “It’s going to be

another hot one. I heard on the radio, it’s a record heat wave. How are your

crops doing?”

“You know how it is. It looked promising this spring. I

thought for sure the hell of the last eight years was past. One good thing,

though. We fought the grasshoppers off this time.”

Egnat’s forehead furrowed. “I thought they’d never leave.”

“At least grain prices have gone up,” the elderly farmer

said, taking off his battered straw hat to wipe his brow.

“A lot of good that will do,” Egnat said, “if we don’t have

any grain worth harvesting.”

The men nodded and took another puff.

The stout farmer nudged the old-timer. “How are you making

out with that lady friend of yours?”

“There may be snow on top, but there’s still fire in the old

furnace.”

The men laughed. Egnat flicked the ash off his cigarette with

his thumbnail, and after ensuring his rollup was no longer lit, put it back in

his shirt pocket. The men smiled at Dunya, who took one last look down the

street before following her brother into the store.

As

usual, the storekeeper, Dan Balacko—a husky young man with dashing

features—flirted with her. “Dunya, you’re a sight to behold. You better watch

all the fellas.” Dan’s eyes roamed over her figure, stopping at her breasts.

Egnat, always protective, said, “Dunya, I need some help in

the back.”

“I’m low on butter. Can you bring some in soon?” Dan asked

Egnat.

“In a day or so,” he replied, before walking away with Dunya.

Together, they picked up fifty-pound bags of flour and sugar and carried them

out to the wagon. Checking the list she got from her mother, Dunya browsed the

store aisles and picked up a box of salt, a cylinder of pepper, a tin of black

tea, and a large spool of black cotton thread.

They waited at the counter while Dan recorded their purchases

under their family name in his ledger. So far, they were good on their credit.

Dan wrote the total on a slip of paper and gave it to Egnat.

Dunya said to Dan, “If you see Peter Klewchuk, tell him Dolly

Mazurec was asking about him. You can also tell him she’s no longer engaged.”

“Is that right?” said Dan, grinning. “It’s Dolly now, is it?

Damn, if I wasn’t already married …”

“Yeah, yeah, yeah,” Dunya said jokingly. Even if Dan was

unattached, she had no interest in him as a potential suitor. He was known as

the town wolf. How much of that was true, she didn’t know. But she believed,

where there’s smoke, there’s fire. A girl couldn’t be too careful.

Thank you for being our

guest once more, Diana. Wishing you tremendous success with your stories.

And thank you Dear Reader & Visitor.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment